Gender digital equality, however defined, is globally worsening rather than improving.[1] This is despite countless initiatives intended to empower women in and through technology.[2] In part, this is because most such initiatives have been developed and run by and for women. When men have been engaged, they have usually mainly been incorporated as “allies” who are encouraged to support women in achieving their strategic objectives.[3] However, unless men fundamentally change their attitudes and behaviours to women (and girls) and technology, little is likely to change. TEQtogether (Technology Equality together) was therefore founded by men and women with the specific objective to change these male attitudes and behaviours. It thus goes far beyond most ally-based initiatives, and argues that since men are a large part of the problem they must also be an integral part of the solution. TEQtogether’s members seek to identify the best possible research and understanding about these issues, and to incorporate it into easy to use guidance notes translated into various different languages. Most research in this field is nevertheless derived from experiences in North America and Europe, and challenging issues have arisen in trying to translate these guidance notes into other languages and cultural contexts.[4] TEQtogether is now therefore specifically exploring male attitudes and behaviours towards women and digital technologies in different cultural contexts, so that new culturally relevant guidance notes can be prepared and used to change such behaviours, as part of its contribution to the EQUALS global initiative on incresing gender digital equality.

Meeting of EQUALS partners in New York, September 2018

Pakistan is widely acknowledged to be one of the countries that has furthest to go in attaining gender digital equality.[5] Gilwald, for example, emphasises that Pakistan has a 43% gender gap in the use of the Internet and a 37% gap in ownership of mobile phones (in 2017).[6] Its South Asian cultural roots and Islamic religion also mean that it is usually seen as being very strongly patriarchal.[7] In order to begin to explore whether guidance notes that have developed in Europe and North America might be relevant for use in Pakistan, and if not how more appropriate ones could be prepared for the Pakistani content, initial research was conducted with Dr. Akber Gardezi in Pakistan in January and February 2020. This post provides a short overview of our most important findings, which will then be developed into a more formal academic paper once the data have been further analysed.

Research Methods

The central aim of our research was better to understand men’s attitudes and behaviours towards women and technology in Pakistan, but we were also interested to learn what women thought men would say about this subject.[8] We undertook 12 focus groups (7 for men only, 4 for women only, and one mixed) using a broadly similar template for both men and women, that began with very broad and open questions and then focused down on more specific issues. The sample included university students and staff studying and teaching STEM subjects (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics), tech start-up companies, staff in small- and medium-sized enterprises, and also in an established engineering/IT company. Focus groups were held in Islamabad Capital Territory, Kashmir, Punjab and Sindh, and they were all approximately one hour in duration. We had ideally wanted each group to consist of c.8-12 people, but we did not wish to reject people who had volunteered to participate, and so two groups had as many as 19 people in them. A total of 141 people participated in the focus groups. The men varied in age from 20-41 and the women from 19-44 years old. All participants signed a form agreeing to their participation, which included that they were participating voluntarily, they could withdraw at any time, and they were not being paid to answer in particular ways. They were also given the option of remaining anonymous or of having their names mentioned in any publications or reports resulting from the research. Interestingly all of the 47 women ticked that they were happy to have their names mentioned, and 74 of the 94 men likewise wanted their names recorded.[9] The focus groups were held in classrooms, a library, and company board rooms. After some initial shyness and uncertainty, all of the focus groups were energetic and enthusiastic, with plenty of laughter and good humour, suggesting that they were enjoyed by the participants. I very much hope that was the case; I certainly learnt a lot and enjoyed exploring these important issues with them.

This report summarises the main findings from each section of the focus group discussions: broad attitudes and behaviours by men towards the use of digital technologies by women; how men’s attitudes and behaviours influence women’s and girls’ access to and use of digital technologies at home, in education, and in their careers; whether any changes in men’s attitudes and behaviours towards women and technology are desirable, and if so how might these be changed. In so doing, it is very important to emphasise that although it is possible to draw out some generalisations there was also much diversity in the responses given. These tentative findings were also discussed in informal interviews held in Pakistan with academics and practitioners to help validate their veracity and relevance.

I am enormously grateful to all of the people in the images below as well as the many others who contributed to this research.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Men’s attitudes and behaviours towards the use of digital technologies by women in Pakistan

When initially asked in very general terms about “women” and “digital technology” most participants had difficulty in understanding what was meant by such a broad question. However, it rapidly became clear that the overall “culture” of Pakistan was seen by both men and women as having a significant impact on the different ways in which men and women used digital technologies. Interestingly, whilst some claimed that this was because of religious requirements associated with women’s roles being primarily in the sphere of the home and men’s being in the external sphere of work, others said that this was not an aspect of religion, but rather was a wider cultural phenomenon.

Both men and women concurred that traditionally there had been differences between access to and use of digital technologies in the past, but that these had begun to change over the last five years. A distinction was drawn between rural, less well educated and lower-class contexts, where men tended to have better access to and used digital technologies more than women, and urban, better educated and higher-class contexts where there was greater equality and similarity between access to and use of digital technologies.

Whilst most participants considered that access to digital technologies and the apps used were broadly similar between men and women, both men and women claimed that the actual uses made of these technologies varied significantly. Men were seen as using them more for business and playing games, whereas women used them more for online shopping, fashion and chatting with friends and relatives. This was reinforced by the cultural context where women’s roles were still seen primarily as being to manage the household and look after the children, whereas men were expected to work, earning money to maintain their families. It is very important to stress that variations in usage and access to technology were not always seen as an example of inequality, but were often rather seen as differences linked to Pakistan’s culture and social structure.

Such views are changing, but both men and women seemed to value this cultural context, with one person saying that “it is as it is”. Moreover, there were strongly divergent views as to whether this was a result of patriarchy, and thus dominated by men. Many people commented that although the head of the household, almost always a man, provided the dominant lead, it was also often the mothers who supported this or determined what happened within the household with respect to many matters, including the use of technology and education.

In the home, at school and university, and in the workplace

Within the home

Most respondents initially claimed that there was little difference in access to digital technologies between men and women in the home, although as noted above they did tend to use them in different ways. When asked, though, who would use a single phone in a rural community most agreed that it would be a male head of household, and that if they got a second phone it would be used primarily by the eldest son. Some, nevertheless, did say that it was quite common for women to be the ones who used a phone most at home.

Participants suggested that similar restrictions were placed on both boys and girls by their parents in the home. However, men acknowledged that they knew more about the harm that could be done through the use of digital technologies, and so tended to be more protective of their daughters, sisters or wives. Participants were generally unwilling to indicate precisely what harm was meant in this context, but some clarified that this could be harassment and abuse.[10] The perceived threats to girls and young women using digital technologies for illicit liaisons was also an underlying, if rarely specifically mentioned, concern for men. There was little realisation though that it was men who usually inflicted such harm, and that a change of male behaviours would reduce the need for any such restrictions to be put in place.

A further interesting insight is that several of the women commented that their brothers are generally more knowledgeable than they are about technology, and that boys and men play an important role at home in helping their sisters and mothers resolve problems with their digital technologies.

At school and university

There was widespread agreement among both men and women that there was no discrimination at school in the use of digital technologies, and that both boys and girls had equal access to learning STEM subjects. Nevertheless, it is clear that in some rural and isolated areas of Pakistan, as in Tharparkar, only boys go to school, and that girls remain marginalised by being unable to access appropriate education.

Boys in rural school in Tharparkar

Furthermore, it was generally claimed that both girls and boys are encouraged equally to study STEM subjects at school, and can be equally successful. Some people nevertheless commented that girls and boys had different learning styles and skill sets. Quite a common perception was that boys are more focused on doing a few things well, whereas girls try to do all of the tasks associated with a project and may not therefore be as successful in doing them all to a high standard.

There were, though, differing views about influences on the subjects studied by men and women at university. Again, it was claimed that the educational institutions did not discriminate, but parents were widely seen as having an important role in determining the subjects studied at university by their children. Providing men can gain a remunerative job, their parents have little preference over what degrees they study, but it was widely argued that traditionally women were encouraged to study medicine, rather than engineering or computer science. Participants indicated that this is changing, and this was clearly evidenced by the number and enthusiasm of women computer scientists who participated in the focus groups. Overall, most focus groups concluded with a view that generally men studied engineering whereas women studied medicine.

In the workplace

There is an extremely rapid fall-off in the number of women employed in the digital technology sector, even if it is true that there is little discrimination in the education system against women in STEM subjects. At best, it was suggested that only a maximum of 10% of employees in tech companies were women. Moreover, it was often acknowledged that women are mainly employed in sales and marketing functions in such companies, especially if they are attractive, pale skinned and do not wear a hijab or head-scarf. This is despite the fact that many very able and skilled female computer scientists are educated at universities, and highly capable and articulate women programmers participated in the focus groups.

Women employed in the tech sector in Pakistan

Part of the reason for this is undoubtedly simply the cultural expectation that young women should be married in their early 20s and no later than 25. This means that many women graduates only enter the workforce for a short time after they qualify with a degree. Over the last decade overall female participation in the workforce in Pakistan has thus only increased from about 21% to 24%, and has stubbornly remained stable around 24% over the last five years.[11]

Nevertheless, the focus groups drilled down into some of the reasons why the digital technology sector has even less participation of women in it than the national average. Four main factors were seen as particularly contributing to this:

- The overwhelming factor is that much of the tech sector in Pakistan is based on delivering outsourced functions for US companies. The need to work long and antisocial hours so as to be able to respond to requests from places in the USA with a 10 (EST) – 13 (PST) hour time difference was seen as making it extremely difficult for women who had household and family duties to be able to work in the sector. There was, though, also little recognition that this cultural issue might be mitigated by permitting women to work from home.

- Moreover, both men and women commented that the lack of safe and regular transport infrastructure made it risky for women to travel to and from work, especially during the hours of darkness. The extent to which this was a perceived or real threat was unclear, and there was little recognition that most threats to women are in any case made by men, whose behaviours are therefore still responsible.

- A third factor was that many offices where small start-up tech companies were based were not very welcoming, and had what several people described as dark and dingy entrances with poor facilities. It was recognised that men tended not to mind such environments, because the key thing for them was to have a job and work, even though these places were often seen as being threatening environments for women.

- Finally, some women commented that managers and male staff in many tech companies showed little flexibility or concerns over their needs, especially when concerned with personal hygiene, or the design of office space, As some participants commented, men just get on and work, whereas women like to have a pleasant communal environment in which to work. Interestingly, some men commented that the working environment definitely improved when women were present.

It can also be noted that there are very few women working within the retail and service parts of the digital tech sector. As the picture below indicates this remains an environment that is very male dominated and somewhat alienating for most women.

Digital technology retail and service shops in Rawalpindi

Changing men’s attitudes and behaviours towards women and technology

The overwhelming response from both men and women to our questions in the focus groups was that it is the culture and social frameworks in Pakistan that largely determine the fact that men and women use digital technologies differently and that there are not more women working in the tech sector. Moreover, this was not necessarily seen as being a negative thing. It was described as being merely how Pakistan is. Many participants did not necessarily see it as being specifically a result of men’s attitudes and behaviours, and several people commented that women also perpetuate these behaviours. Any fundamental changes to gender digital inequality will therefore require wider societal and cultural changes, and not everyone who participated in the focus groups was necessarily in favour of this.

It was, though, recognised that as people in Pakistan become more affluent, educated and urbanised, and as many adopt more global cultural values, things have begun to change over the last five years. It is also increasingly recognised that the use of digital technologies is itself helping to shape these changed cultural values.

A fundamental issue raised by our research is whether or not the concern about gender digital equality in so-called “Western” societies actually matters in the context of Pakistan. Some, but by no means all, clearly thought that it did, although they often seemed more concerned about Pakistan’s low ranking in global league tables than they did about the actual implications of changing male behaviour within Pakistani society.

Many of the participants, and especially the men, commented that they had never before seriously thought about the issues raised in the focus groups. They therefore had some difficulty in recommending actions that should be taken, although most were eager to find ways through which the tech sector could indeed employ more women. Both men and women were also very concerned to reduce the harms caused to women by their use of digital technologies.

The main way through which participants recommended that such changes could be encouraged were through the convening of workshops for senior figures in the tech sector building on the findings of this research, combined with much better training for women in technology about how best to mitigate the potential harm that can come to them through the use of digital technologies.

Following the main focus group questions, some of the participants expressed interest in seeing TEQtogether’s existing guidance notes. Interestingly, they commented that many of the generalisations made in them were indeed pertinent in the Pakistani context, although some might need minor tweeking and clarification when translated into Urdu.

However, two specific recommendations for new guidance notes were made:

- Tips for CEOs of digital tech companies who wish to attract more female programmers and staff in general; and

- Guidance for brothers who wish to help their sisters and mothers gain greater expertise and confidence in the use of digital technologies.

These are areas that we will be working on in the future, and hope to have such guidance notes prepared in time for future workshops in Pakistan in the months ahead.

Several men commented that improving the working environment for women in tech companies, and enabling more flexible patterns of work would also go some way to making a difference. Some commented how having more women in their workplaces had already changed their behaviours for the better.

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to colleagues in COMSATS University Islamabad (especially Dr. Tahir Naeem) and the University of Sindh (especially Dr. M.K. Khatwani) for facilitating and supporting this research. We are also grateful to those in Riphah International University (especially Dr. Ayesha Butt) and Rawalpindi Women University (especially Prof Ghazala Tabassum), as well as those companies (Alfoze and Cavalier) who helped with arrangements for convening the focus groups. Above all, we want to extend our enormous thanks to all of the men and women who participated so enthusiastically in this research. It was an immense pleasure to work with you all.

[1] Sey, A. and Hafkin, N. (eds) (2019) Taking Stock: Data and Evidence on Gender Equality in Digital Access, Skills, and Leadership, Macau and Geneva: UNU-CS and EQUALS; OECD (2019) Bridging the Digital Gender Divide: Include, Upskill, Innovate, Paris: OECD;

[2] See for example the work of EQUALS which seeks to bring together a coalition of partners working to reduce gender digital equality.

[3] See for example, Manry, J. and Wisler, M. (2016) How male allies can support women in technology, TechCrunch; Johnson, W.B. and Smith, D.G. (2018) How men can become better allies to women, Harvard Business Review.

[4] Especial thanks are due to Silvana Cordero for her important contribution on the specific challenges of translation in Spanish in the Latin American context.

[5] Siegmann , K.A. (no date) The Gender Digital Divide in Rural Pakistan: How wide is it & how to bridge it? Sustainable Development Policy Institute (SDPI)/ISS; Tanwir, M. and Khemka, N. (2018) Breaking the silicon ceiling: Gender equality and information technology in Pakistan, Gender, Technology and Development, 22(2), 109-29; see also OECD (2019) Endnote 1.

[6] Gilwald, A. (2018) Understanding the gender gap in the Global South, World Economic Forum,

[7] Chauhan, K. (2014) Patriarchal Pakistan: Women’s representation, access to resources, and institutional practices, in: Gender Inequality in the Public Sector in Pakistan. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

[8] This research builds on our previous research in Pakistan published as Hassan, B, and Unwin, T. (2017) Mobile identity construction by male and female students in Pakistan: on, in and through the ‘phone, Information Technologies and International Development, 13, 87-102; and Hassan, B., Unwin, T. and Gardezi, A. (2018) Understanding the darker side of ICTs: gender, harassment and mobile technologies in Pakistan, Information Technologies and International Development, 14, 1-17.

[9] All names will be listed with appreciation in reports submitted for publication.

[10] Our previous research (Hassan, Unwin and Gardezi, 2018) provides much further detail on the precise types of sexual abuse and harassment that is widespread in Pakistan.

[11] https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Pakistan/Female_labor_force_participation/

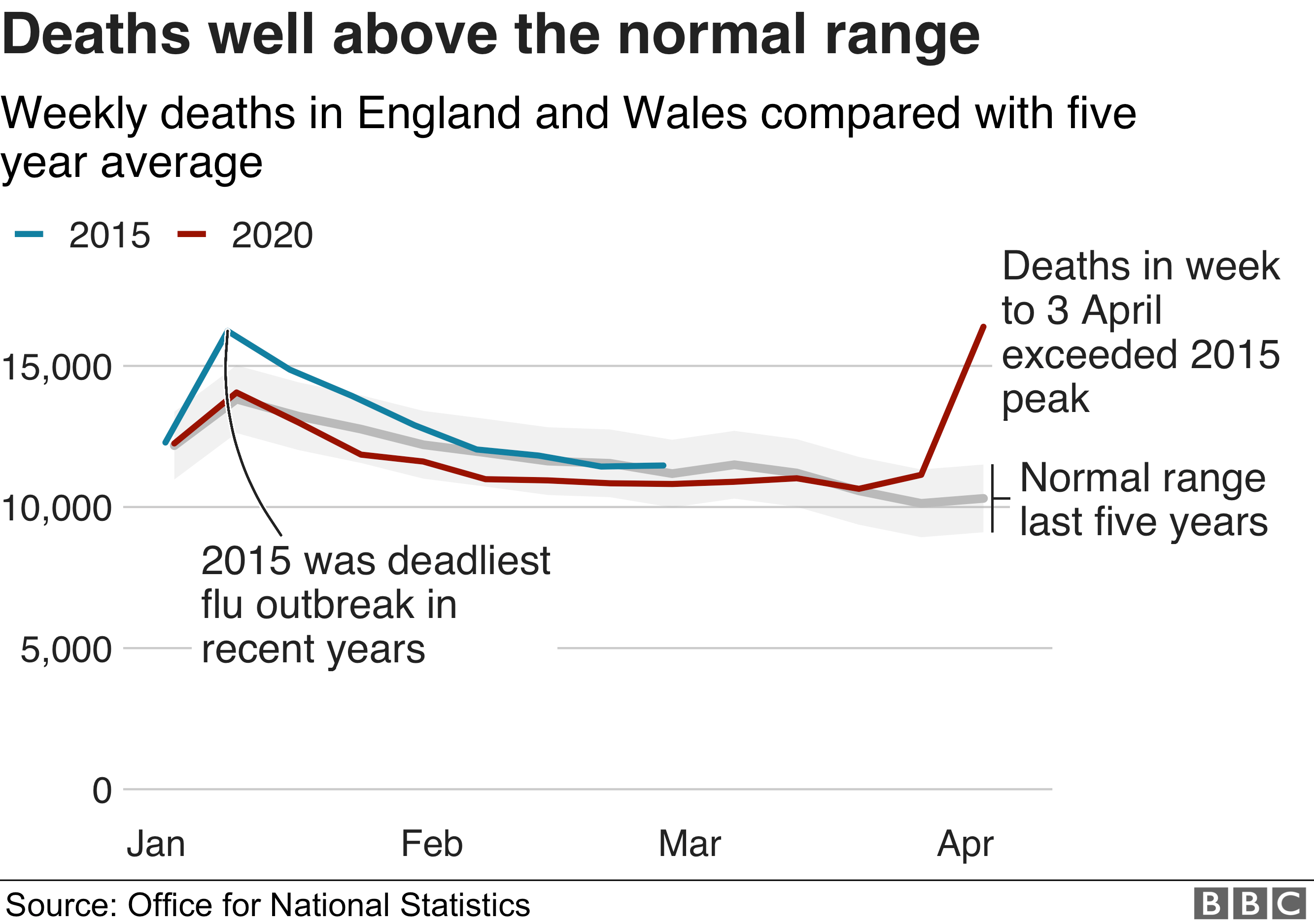

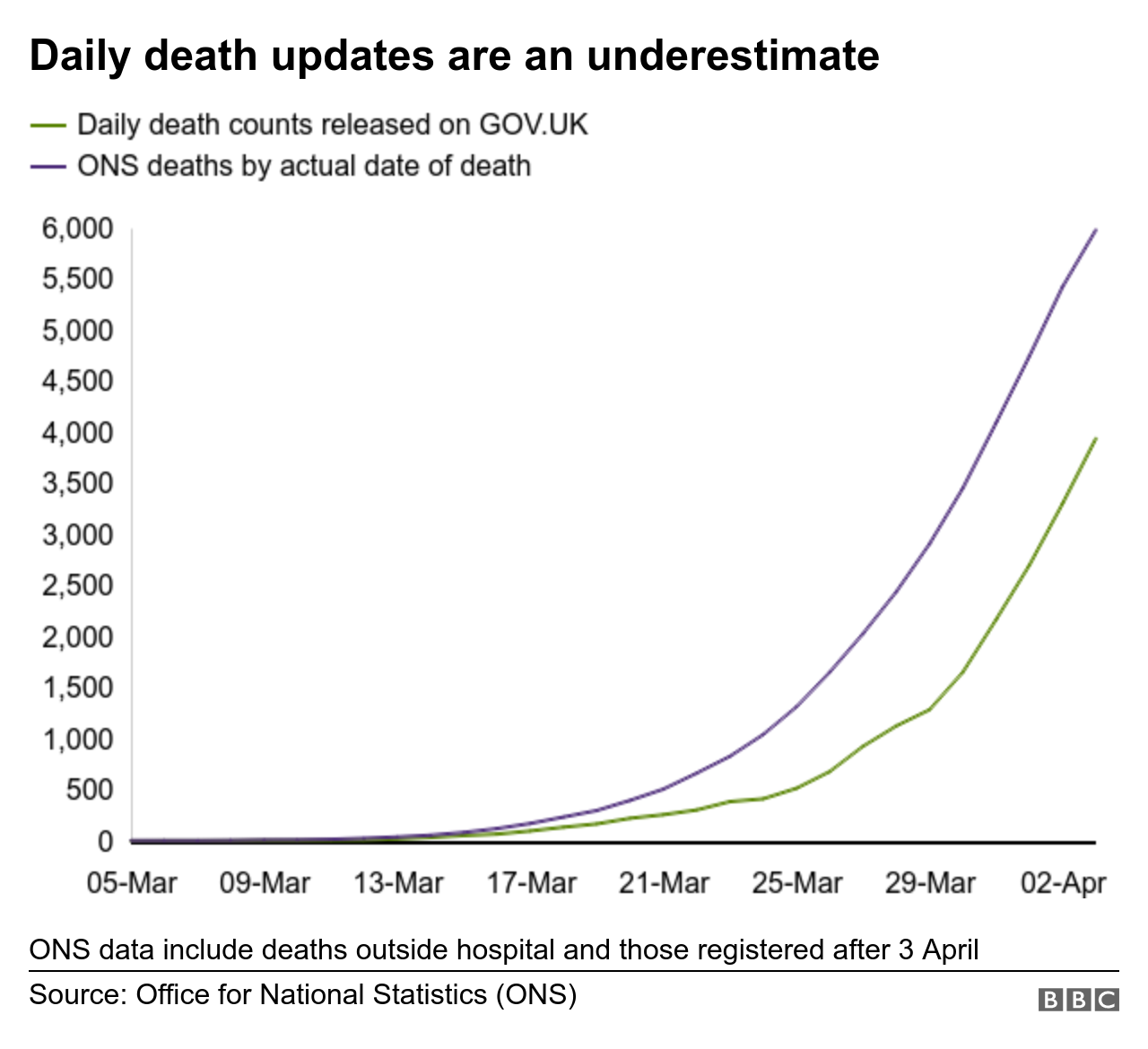

I have held off writing much that is overtly critical of the UK government’s handling of the Covid-19 pandemic, but can do so no longer. We have known for a long time that data published by governments across the world about infections is highly unreliable, although figures on deaths are somewhat more representative of reality. The UK governments’s lack of transparency, though, about its Covid-19 data is deeply worrying, and suggests deliberate deceipt. The following observations may be noted about the figures that are currently being published, and the ways in which official (and social) media use them.

I have held off writing much that is overtly critical of the UK government’s handling of the Covid-19 pandemic, but can do so no longer. We have known for a long time that data published by governments across the world about infections is highly unreliable, although figures on deaths are somewhat more representative of reality. The UK governments’s lack of transparency, though, about its Covid-19 data is deeply worrying, and suggests deliberate deceipt. The following observations may be noted about the figures that are currently being published, and the ways in which official (and social) media use them.

Once there was a brilliant young entrepreneur living in Africa. Let us call him Alfred. He wanted to make loads of money, but was also very committed to trying to improve the quality of girls’ learning and education. One evening, drinking probably too much Tusker, Alfred had a stroke of inspiration. What if he could persuade the government that giving girls high quality new running shoes would transform the quality of their learning experience, and thus their future job prospects. This was an absolute no brainer. The government would have to buy his trainers for every girl in the school system!

Once there was a brilliant young entrepreneur living in Africa. Let us call him Alfred. He wanted to make loads of money, but was also very committed to trying to improve the quality of girls’ learning and education. One evening, drinking probably too much Tusker, Alfred had a stroke of inspiration. What if he could persuade the government that giving girls high quality new running shoes would transform the quality of their learning experience, and thus their future job prospects. This was an absolute no brainer. The government would have to buy his trainers for every girl in the school system!

It was great to be part of the DFID-funded technology for education

It was great to be part of the DFID-funded technology for education